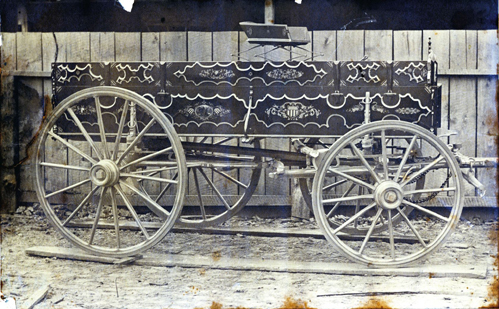

The panels on the sideboards of the wagon box include meticulous pin striping combined with hand painted landscapes and patriotic crests depicting a 19th century flag and shield. Three dimensional carved wood designs are also affixed to the side panels. Overall, the metal and woodwork is artistically contoured and the paint is polished to a mirror-like finish. Even the stay chains are intricately twisted. Early on, we determined that this ornately decorated farm wagon was built as a showpiece or exhibition-style wagon.

Some of its most distinctive features include brakes designed to engage the front wheels instead of the rear. Additionally, the rear hound is attached directly to the back of the front hound at a single pivot point instead of being fastened by a reach or coupling pole as with a traditional farm, freight or ranch wagon.

Some of its most distinctive features include brakes designed to engage the front wheels instead of the rear. Additionally, the rear hound is attached directly to the back of the front hound at a single pivot point instead of being fastened by a reach or coupling pole as with a traditional farm, freight or ranch wagon.

Above the hounds, an independent reach is connected to the front and rear bolster. This particular reach, axle and articulating gear design is interesting because it permits both axles to turn simultaneously in opposite directions when the tongue is steered one way or the other. (Note in the photos how the rub irons are positioned just in front of the rear wheel as well as the traditional location behind the front wheel.) The effect allows the wagon to turn in an extremely small space. Similar technology was ultimately used in wagon gears designed for fruit orchards and some vintage carriage manufacturers also experimented with a twin axle steering system but the idea never gained a strong following. Interestingly, a variation of this idea was offered in Chevrolet trucks a few years ago and it, too, met with only modest success.

Beyond these primary observations, we quickly came to a standstill in our search for more information on this specific wagon and photo. Working from the only written clues we had, we pursued the notations credited to Seymour, Indiana and the Centennial. While the Indiana Centennial occurred in 1916, we found no solid indications of a wagon built like this and shown during that celebration. In fact, the elements of this image appeared to hearken from a former time. The vintage mount, itself, would seem more representative of earlier photo styles. Combined with the unlikelihood that an elaborate wagon design such as this would come from an era when automobiles were already putting so many horse drawn vehicle makers out of business, we were led to focus elsewhere. Looking back even farther to the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, we were, again, left with more questions than answers.

Time and persistence, though, have a way of opening doors. Such was the result when we recently discovered an 1877 work entitled, “The Carriage Builders’ Reference Book.” Printed by I.D. Ware, publisher of The Carriage Monthly magazine of that time, the book includes a section which profiles the vehicle makers participating in the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. Certainly, for any carriage or wagon maker, a presence at this first “World’s Fair” would have been a huge promotional opportunity.

Beyond these primary observations, we quickly came to a standstill in our search for more information on this specific wagon and photo. Working from the only written clues we had, we pursued the notations credited to Seymour, Indiana and the Centennial. While the Indiana Centennial occurred in 1916, we found no solid indications of a wagon built like this and shown during that celebration. In fact, the elements of this image appeared to hearken from a former time. The vintage mount, itself, would seem more representative of earlier photo styles. Combined with the unlikelihood that an elaborate wagon design such as this would come from an era when automobiles were already putting so many horse drawn vehicle makers out of business, we were led to focus elsewhere. Looking back even farther to the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, we were, again, left with more questions than answers.

Time and persistence, though, have a way of opening doors. Such was the result when we recently discovered an 1877 work entitled, “The Carriage Builders’ Reference Book.” Printed by I.D. Ware, publisher of The Carriage Monthly magazine of that time, the book includes a section which profiles the vehicle makers participating in the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. Certainly, for any carriage or wagon maker, a presence at this first “World’s Fair” would have been a huge promotional opportunity.

The event was a massive undertaking as it was meant to be a salute to the 100th Anniversary of the signing of America’s Declaration of Independence. As such, it was a showcase of U.S. ingenuity, pointing to an even brighter future through the country’s industrial leadership and achievements. Hundreds of acres were set aside in the historic city of brotherly love for construction of more than 200 buildings including hotels, exhibition halls and food services as well as massive structures highlighting technology from 26 states and a dozen nations. Transportation around the Exposition included what is purported to be the first elevated monorail railway in the United States. Among the thousands of exhibits were Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone, a mechanical calculating machine (a precursor to today’s computers), a Remington typewriter and countless other 19th century advancements*. The right forearm, hand and flame of the Statue of Liberty was displayed as a way for the French sculptor, Frederic Bartholdi, to bring greater awareness of the French gift to America and help finance a pedestal for the finished work. It would be another decade before the statue was officially presented to the U.S. as a monument to independence. The Exposition and all of its festivities lasted for six months and touted more than 10 million visitors before its closing in November of 1876. Put in its historical context, the Exposition was only a month and a half old when General Custer and the 7th Cavalry met their demise at the Battle of the Little Big Horn. Three months before the Exposition ended, Wild Bill Hickok would also meet his end in Deadwood, South Dakota. History and the country were both moving rapidly during this 100th birthday year.

Along with information on the Exposition, carriage makers profiled in “The Carriage Builders’ Reference Book” were credited with exhibiting over 250 new horse drawn vehicles at the event. Additionally, the book profiles more than 30 different wagon manufacturers who displayed 78 wagons at the Exposition. While many of the builders were well known national or extremely strong regional brands, there were a few smaller makers in the group who were obviously hoping to increase the size and scope of their vehicle business through the added attention of the Centennial festivities. Within the wagon section, we noted a particular builder with a different approach to wagon design and construction. His name was Jacob Becker, Jr. He hailed from Seymour, Indiana and, according to the written review he, “Displayed a farm wagon with his patent gearing…The perch was coupled to a bar running across the back part of the front gearing, and when the front wheels were turned in one direction, the back wheels were thrown at the same time in the opposite direction, thus allowing the wagon to turn in a very short space.” Suddenly, the old Centennial wagon photo that had stumped us for years seemed to have some light shed on its identity. This description, alone, overlaid the vintage photo and penciled title perfectly; giving us plenty of reason to believe the wagon in the image was likely built by Jacob Becker. Fortunately, there was even more solid evidence confirming Becker as the maker.

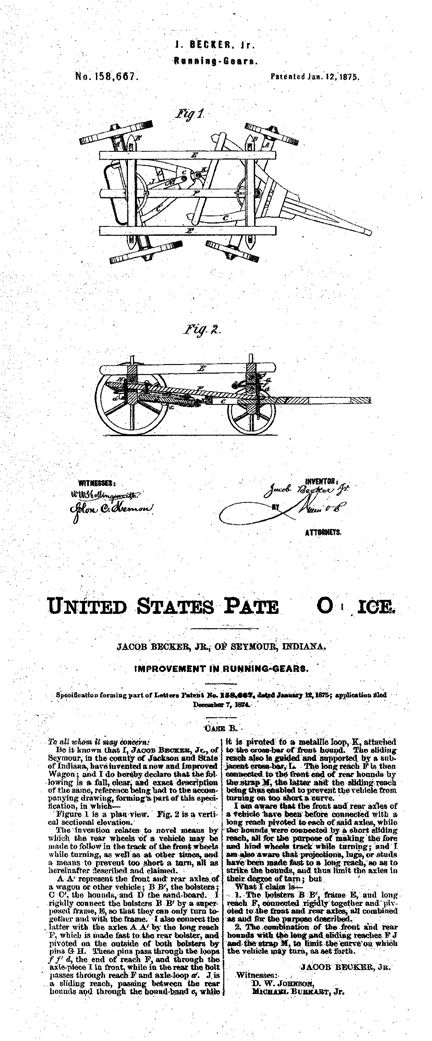

In the wagon description, the writer mentions a “patent” gear. A cursory search of patents issued in the 1870’s turned up not just one, but two, for the same Jacob Becker, Jr. of Seymour, Indiana. Mr. Becker’s first application for a patent was submitted on November 27, 1874 and was granted less than three months later on February 9, 1875. It dealt with several wagon design features including the invention of a new braking system with brake blocks mounted just behind the front wheels. In downhill travel, the brake was engineered to automatically take hold as the horses slowed and the tongue began to rise. A system of levers engaged the brake and it could be manually overridden when the wagon was being backed up. This feature can clearly be seen on the old photo.

In the wagon description, the writer mentions a “patent” gear. A cursory search of patents issued in the 1870’s turned up not just one, but two, for the same Jacob Becker, Jr. of Seymour, Indiana. Mr. Becker’s first application for a patent was submitted on November 27, 1874 and was granted less than three months later on February 9, 1875. It dealt with several wagon design features including the invention of a new braking system with brake blocks mounted just behind the front wheels. In downhill travel, the brake was engineered to automatically take hold as the horses slowed and the tongue began to rise. A system of levers engaged the brake and it could be manually overridden when the wagon was being backed up. This feature can clearly be seen on the old photo.

The second patent was filed on December 7, 1874 and granted five weeks later on January 12, 1875. This additional patent dealt with the twin axle turning feature of the gear which allowed the rear wheels to follow in the tracks of the front wheels and also prevented the vehicle from turning too short. Enhancing this turning system, the bolsters were connected to a frame/wagon box so they could move with the frame – thus allowing the independent rotation of the axles. Also part of this patent is a separate reach connected to the bolsters and a metallic loop that created a pivot point between the front and rear hounds. Both of these features can easily be seen in the old photo. By this point, we knew we had made the connection between wagon and maker. Encouraged by the breakthrough of information, we wanted to know even more about Jacob Becker, Jr.

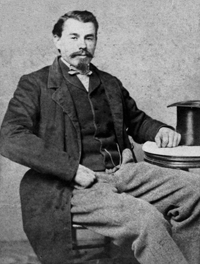

Commissioning the talents of an accomplished genealogist, we were quickly led to family members who, amazingly, not only possess photos of Jacob Becker, but a silver medal he won from the state of Indiana in 1875 for his unique wagon designs. They also own an original copy of one of the miniature patent models originally built in 1874. While the family had always been aware of Mr. Becker’s patent achievements, they had never seen one of his wagons or known of his actual wagon-making ventures or his display at the 1876 Centennial Exposition.

The process of putting an accurate identity to this previously unknown 19th century image has literally been akin to finding a needle in a haystack. As with all lost and then found treasures, this was another exciting discovery for our Wheels That Won The West® archives. Equally important, it has helped the Becker family draw closer to their roots while simultaneously restoring another vital part of our early American transportation history. But, even with so much uncovered, there are still questions. Where is the wagon today? Has it survived the passage of time? Were any other wagons built using the patented technology and what happened to the Seymour firm?

Certainly with all we’ve learned, there is still more to be discovered about Mr. Becker and his unique Centennial wagon. We started with the acquisition of a one-of-a-kind photo. Now, more than two years later, we’ve followed the trail to an all-but-forgotten 19th century wagon maker. We are especially grateful to the anonymous individual that, more than a century ago, wrote “Seymour Centennial Wagon” on the back of the old photo. That single act has reaffirmed the value of identifying photos as they are taken and it has been a significant key to unlocking the mystery of this image.

Commissioning the talents of an accomplished genealogist, we were quickly led to family members who, amazingly, not only possess photos of Jacob Becker, but a silver medal he won from the state of Indiana in 1875 for his unique wagon designs. They also own an original copy of one of the miniature patent models originally built in 1874. While the family had always been aware of Mr. Becker’s patent achievements, they had never seen one of his wagons or known of his actual wagon-making ventures or his display at the 1876 Centennial Exposition.

The process of putting an accurate identity to this previously unknown 19th century image has literally been akin to finding a needle in a haystack. As with all lost and then found treasures, this was another exciting discovery for our Wheels That Won The West® archives. Equally important, it has helped the Becker family draw closer to their roots while simultaneously restoring another vital part of our early American transportation history. But, even with so much uncovered, there are still questions. Where is the wagon today? Has it survived the passage of time? Were any other wagons built using the patented technology and what happened to the Seymour firm?

Certainly with all we’ve learned, there is still more to be discovered about Mr. Becker and his unique Centennial wagon. We started with the acquisition of a one-of-a-kind photo. Now, more than two years later, we’ve followed the trail to an all-but-forgotten 19th century wagon maker. We are especially grateful to the anonymous individual that, more than a century ago, wrote “Seymour Centennial Wagon” on the back of the old photo. That single act has reaffirmed the value of identifying photos as they are taken and it has been a significant key to unlocking the mystery of this image.

Jacob Becker, Jr.

Photo courtesy of Philip Becker.

From what we’ve been able to gather, Mr. Becker was around 33 years old during the Exposition in Philadelphia. Genealogical records show that he emigrated from Bavaria to the United States in 1866. He is listed in the 1870 and 1880 Jackson County, Indiana censuses as a wagon maker and city directories still show his business in Seymour as late as 1886. Unfortunately, the 1890 census results were destroyed by fire, but by 1888, wagon industry directories do not include him among the wagon makers in Seymour. There are indications that several tragedies hit the Becker family during this timeframe and may have resulted in Becker closing or selling his wagon firm.

Silver medal Jacob Becker, Jr. won from the sate of Indiana in 1875 for his unique wagon designs.

Photo courtesy of John Becker.

Clearly, Jacob Becker, Jr. was a visionary who dared to dream and he made those dreams part of the biggest celebration in the world. We’ve yet to determine whether it brought him any financial success. But after more than one hundred thirty years, this aging and fragile photo has done more than any of his other efforts could. Like a pass into the Centennial Exposition itself, the image has become Jacob Becker’s ‘ticket to tomorrow,’ bringing him once again into the limelight while firmly securing his place of prominence among America’s early vehicle makers. WTWTW

Editor's Note

Editor's Note

According to the “1877 Carriage Builders’ Reference Book,” Studebaker had the largest number of wagons shown at the Exposition. Included in their exhibit was a huge freight wagon said to have a carrying capacity of 14 tons. Also on display in the Studebaker section was a ‘Centennial’ labeled farm wagon that won a Gold medal and First Award of Merit during the festivities. This same Centennial wagon has survived and is currently on exhibit at the Studebaker Museum in South Bend, Indiana. You can see this wagon in our ‘Legacy’ collection located in the Gallery section at the top of the “Wheels That Won The West” homepage or simply visit the museum at www.studebakermuseum.org. As of this writing, the only photos we know to exist of wagons shown at the 1876 Centennial are those of this Studebaker and our rare image of the Jacob Becker, Jr. wagon. If someone knows of other images or surviving Centennial vehicles, please contact or write us at info@wheelsthatwonthewest.com

David Sneed is an early western vehicle historian, writer, collector, speaker, and founder of the Wheels That Won The West® Archives. Unless otherwise indicated, all text and imagery is Copyright © David E. Sneed, All Rights Reserved